Can you think of 10 creative ways to use scissors?

If you’re like most people, you probably can barely think of a couple of ways to use scissors other than cutting.

When we use objects for a specific purpose, our brain associates them with that activity and is blocked if it has to find other unusual and more original functions. The same thing happens in our day to day, either when we get carried away by habits and routines or when we see a person from a single perspective. Without realizing it, functional fixedness limits our life, a life that is constantly changing, for which reason it demands a great deal of flexibility to adapt, avoid blows and take advantage of opportunities.

What does the candle problem teach us?

Functional Fixedness is a cognitive bias that affects our ability to be creative and flexible. In the framework of problem solving, it refers to the inability to think outside the established limits and find original solutions. However, in a broader context it is used to refer to people who are too attached to habits and customs who lack the necessary flexibility to adapt to changes.

The concept of Functional Fixedness was created around 1935 by the Gestalt therapist Karl Duncker. During his studies on cognition and problem solving, he noted that while Functional Fixedness is a necessary cognitive and perceptual skill, in some cases it hinders problem solving and kills creativity.

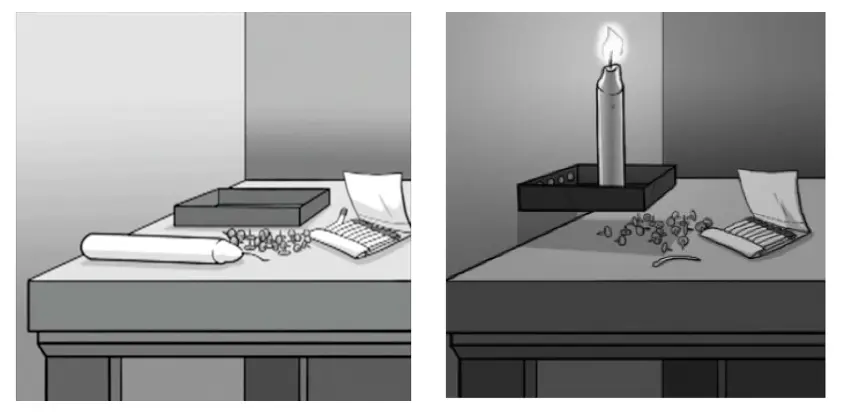

Later, in 1945, he developed the famous “candle problem.” In the experiment, he asked participants to figure out how to affix a candle to a cork board and light it without the wax could drip onto the table below. To do so they had a box of matches and some thumbtacks. Obviously, they needed to fix the problem as quickly as possible.

Many people tried creative solutions without success, such as trying to tack the candle to the wall. Others melted the end of the candle and tried to stick it to the wall. Only a few discovered the solution: empty the box of thumbtacks, tack it to the corkboard, and place the upright candle inside the box before lighting it.

From this experiment, Duncker deduced that people have difficulty solving a problem when an object has a fixed function, which must be changed to find a solution. In this case, the successful people realized that the box was not just a container for the tacks, but could also double as a candle holder to catch the wax that dripped from the burning candle.

Interestingly, when Duncker repeated the experiment by placing the thumbtacks outside the box, more people discovered the solution. Changing a simple detail reduced Functional Fixedness by helping people see things from a broader and more creative perspective.

The terrible effects of Functional Fixedness in our lives

Functional Fixedness affects negatively our ability to creatively solve problems, innovate, and adapt to change. This bias makes us see the situation or the problem from only one point of view, limiting our flexibility, which is why it becomes a barrier to finding new solutions and developing different perspectives.

In the long run, this fixedness restricts our ability to recognize alternative approaches, limits our options and condemn us to trip over and over again with the same stone, generating a high dose of frustration. In fact, Functional Fixedness can manifest itself in any area of our lives, from the professional to our relationships.

In reality, Functional Fixedness is disastrous for our relationships. When we get used to seeing persons in a certain way, we lock them into a role and attribute certain characteristics to them, which is why it is usually more difficult to address conflicts and discrepancies. When the perspective with which we look at persons is too narrow, we can even caricature them, which limits our ability to feel empathy and understand them, especially when they do not behave in a manner coherent with the preconceived ideas we have about them.

However, Functional Fixedness does not only affect people. This bias can also be seen at the societal level, in which case it has systemic effects. When mental rigidity becomes the norm, it prevents innovation, condemning societies to immobility and passivity. It also becomes an obstacle to solving its most pressing problems, since it pushes the different groups that compose it to maintain the status quo and do things as they have always been done. That often leads us into a downward social spiral.

Why does Functional Fixedness occur?

We can all fall into the Functional Fixedness trap, but this cognitive bias tends to get stronger as we get older. A study conducted at the University of Essex, for example, found that 5-year-olds children did not show early signs of Functional Fixedness when solving problems. However, by the age of 7 children already used to see objects as if they were meant to be used in one way and not another, which opened the doors to Functional Fixedness.

Younger people have some initial immunity to this bias due to their lack of experience, which allows them to be more creative in their search for solutions. In fact, Functional Fixedness has been shown to consolidate as we gain more experience in problem solving.

Ironically, the more practice we get in identifying solutions to a problem, the more difficult it will be for us to find alternative or more creative solutions. Although we are aware that our traditional method of solving a problem may not be effective, we are still tempted to use the same approach simply because we are familiar with those strategies and are too lazy to explore other ways.

How to overcome Functional Fixedness?

As with many cognitive biases, Functional Fixedness can appear at any time and affect different areas of our lives. To overcome it, we need to make a conscious effort.

The first step in overcoming Functional Fixedness is to develop awareness of the problem and make it as simple as possible. By removing the inconsequential details we can think more creatively about the solution.

For example, if we want to transplant a plant, Functional Fixedness will immediately lead us to look for a pot, but if we don’t find it, we will block ourselves. On the other hand, if we abstract the problem, so that we don’t think we need a pot but an object that can contain a plant, a new world of possibilities opens up.

In fact, it is important to properly frame the problem and not judge or dismiss ideas that come to mind too soon, no matter how far-fetched they may seem, as they may contain the seed of a solution. The key is to broaden the perspective on the different factors involved in the situation that we must face. In the candle problem, for example, just stop thinking of the thumbtack box as a tack container and start seeing it simply as a container. When we manage to go beyond the concrete and functional level, our horizon expands.

To overcome functional fixation we should also look for inspiration in unexpected places. When we move into domains seemingly unrelated to the original problem, we are more likely to find creative solutions by mixing ideas or simply allowing the mind to relax and think more freely. Looking in other directions will always open our perspective, allowing us to be more original and creative in all areas of life.

Sources:

German, T. P. & Defeyter, M. A. (2000) Immunity to Functional Fixedness in Young Children. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review; 7: 707-712.

Glucksberg, S. (1962) The influence of strength of drive on functional fixedness and perceptual recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology; 63(1): 36-41.

Duncker, K. (1945) On problem-solving (L. S. Lees, Trans.) Psychological Monographs; 58(5): i–113.