There are times when either fear or anger, turn us completely blind and make us act in a way that otherwise we would never do. At such times, we can use harsh words that hurt others and we commit reprehensible acts. We react in an exaggerated manner, without thinking, we lose control of the situation and ourselves. At that time occurs an emotional hijacking.

What is an emotional hijacking?

All of us, sooner or later, we have been victims of these emotional hijackings. There are times when we stop thinking, we’re carried away by feelings and, after that critical moment, we do not remember very well what we did or why.

When we are victims of an emotional outburst, the center of the limbic system declares a “state of emergency” and recruits all the resources of the brain to perform its functions. That seizure occurs within a few seconds and creates an immediate reaction in the prefrontal cortex, the area associated with reflection, and we have no time to evaluate what is happening and decide rationally.

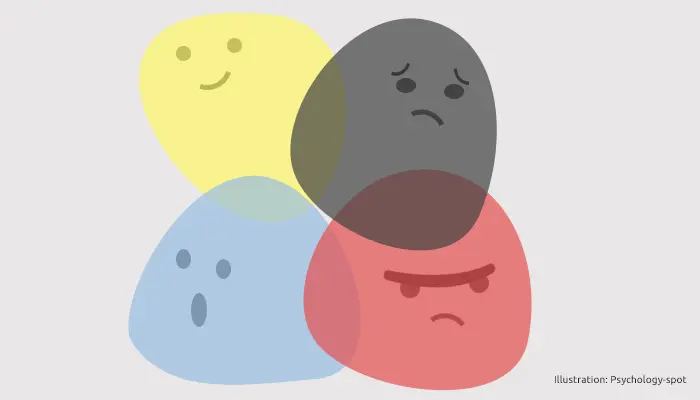

Obviously, all emotional hijackings have negative connotations. For example, when we are victims of an attack of uncontrollable laughter or feel euphoric, the amygdala also takes control and prevents us from thinking. In fact, is not the first time (and won’t be the last) that someone makes a stupid thing, moved by a state of euphoria, promising things that will not satisfy.

The amygdala: Headquarter of passions and brain sentinel

The emotional hijacking is generated in the amygdala, which is one of the most important structures of the limbic system, where emotions are processed. In fact, the amygdala is specialized in the processing of emotional stimuli factors, and is linked to the process of learning and memory. It has been seen that when occurs a disconnection between the amygdala and the rest of the brain, we are not able to give an emotional meaning to the situation. For example, we can see our partner but do not experience any emotion. Thus, the amygdala is a kind of reservoir of emotional memory.

However, the amygdala plays a fundamental role in passions. When this structure is damaged, people have no feelings of anger and fear. They are not even able to mourn.

At this point you might wonder: if the amygdala works perfectly, how can we get carried away by passion so easily?

The problem is that the amygdala also plays the role of sentinel of our brain and one of its functions is to examine the perceptions in search of a threat. The amygdala reviews each situation wondering if: Is it something I hate? Can it hurt me? Would I fear it? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the amygdala reacts immediately activating all the resources and sends an emergency message to the rest of the brain. These messages are triggering the secretion of a number of hormones that prepare us to flee or fight.

At this time the muscles tighten, the senses are sharpened and we turn on alert. The memory system is also activated to try to recover any information that may be useful to get out of that risk. Thus, when we face potential danger, the amygdala takes over and runs almost the entire mind, even the rational part.

Of course, in our brain everything is ready to give free rein to the amygdala because when we are in danger, nothing else matters. Therefore, the amygdala is the first cerebral station through which run the signals coming from our senses, only after being assessed they pass to the prefrontal cortex. That is why, sometimes emotions go beyond us taking the control.

Failure to activate the rational mind

Because an emotional hijacking occurs, it is not sufficient that the amygdala be activated, it is also necessary a failure in the activation of the neocortical processes that are responsible for balancing our emotional responses. In fact, it is usual that when the rational mind is overloaded with the emotional mind, the prefrontal cortex is activated to help manage emotions and to evaluate possible solutions.

The right prefrontal lobe is the seat of negative feelings such as fear and aggression, while the left prefrontal lobe keeps them at bay, serving as a kind of neural thermostat that allows us regulating the unpleasant emotions. During an emotional hijacking, the left prefrontal lobe is simply turned off letting the emotions flow.

One of the main problems of this neural alarm system is that in the world in which we now live, where there aren’t serious dangers threatening our lives, it is almost never necessary for the amygdala to hijack the rest of the brain. Especially when you consider that, when the amygdala is activated, it performs very crude associations with small pieces of past experiences. So that, if a person has developed a deep fear of the sound of firecrackers any similar sound can trigger an emotional hijacking.

In fact, the low accuracy of our emotional brain becomes even stronger when you consider that many of our memories are from our childhood, when structures such as the amygdala and hippocampus had not yet fully matured and could store information with excessive emotional charge.

At this point, we should not be surprised if some of our most intense emotional reactions are incomprehensible to us, as these could come from some event of our childhood in which the world still was too chaotic and when we even hadn’t acquired the language yet. At that point, any experience may have been recorded in an immature amygdala as a trauma, which can later be activated in similar situations.

Is it possible to avoid the emotional hijacking?

There are some situations where it is virtually impossible to avoid an emotional hijacking. However, that does not mean we should resign to be passive victims of our emotions. On the contrary, we can train our brain to learn to discriminate between signals that actually represent a danger and others which are harmless.

How to do it?

First, being aware that most situations of everyday life can be stressful or frightening but do not represent a real danger. Therefore, there’s no need to be tense or angry.

Moreover, it is necessary to practice detachment, in the sense that, the more possessions we consider as part of our “ego”, the more we will have the tendency to overreact when they are endangered.

Source:

Goleman, D. (1996) Emotional Intelligence, Random House.